The Illusion of Self

How Our Perception of Time Gives Rise to The Ego

Key Takeaways

The ego is the mental reflection of the physical body, and though it’s a helpful construct, it’s entirely illusory.

Swapping the temporal dimension for a physical one, as one does when reading sheet music, reveals the illusory nature of the individual self.

The illusory nature of the ego reveals a specific geometry of the career of humankind, and that geometry, in turn, suggests a particular moral imperative.

The Illusion of Ego

The Apology is Plato's account of the speech Socrates gave in his own defense at his trial in 399 BC. Apology comes from the Greek word “apologia”, which means a formal, reasoned defense. Not an admission of wrongdoing.

Plato described his mentor saying in his defence that he has an inner daimonion (often translated as "daemon," "divine voice," or "inner oracle"), whom he consults on matters of right and wrong. He described himself as being in discourse with his conscience. Much like Pinocchio consulting Jiminy Cricket, the personification of his conscience.

Another Disney movie, the Pixar film Inside Out, portrays multiple inner voices personified. In the movie, characters representing a little girl’s competing emotions interact with each other inside her head. The movie works because we all have multiple voices inside our heads, just like Socrates. When you ask yourself, “What did I just come into this room to get?”, who are you talking to?

Each of our minds is a cluster of competing voices. But because we MUST interact with each other in physical space, we’re forced to assume a convenient 1:1 ratio between minds and bodies. In essence, we throw a tablecloth over each little cluster of competing voices and regard each as a discrete individual.

These tablecloths are frameworks that package a variety of subpersonalities into a single identity; it is the ego. Though it’s the most useful of fictions, your ego is entirely a mental construct. The late ethnobotanist Terence McKenna loved to define the ego as the tool we use to know which mouth to feed at the dinner table. It’s the mental reflection of your physical body. You walk around all day behaving as if this reflection is really you, but it’s actually just a phantom. You are no more your ego than you are your reflection in the mirror.

The Broccoli Analogy

To understand the illusion of ego on a deeper level, let’s look at it through the lens of time and space.

Beethoven’s symphonies are conventionally experienced in a concert hall as sound. But they can also be visually experienced as sheet music. Because sheet music represents time as a physical dimension, lengthy sequences of notes, which take minutes to hear, are instantly visible at a glance. Those who read music can identify different symphonies by listening OR by seeing.

This trick of swapping time (measured with a stopwatch) for distance (measured with a ruler) presents an interesting thought experiment. If you swapped these dimensions in your own life, your body as it exists in each moment—from infancy to old age—would similarly be visible at a glance.

From that bizarre perspective, you’d appear to be bodily connected to both your ancestors and to any descendants you might have. That’s because, at some point in the past, every person on the planet shared a body with their mother. Motherhood is the forking of a single individual into two or more individuals, just as a tree trunk forks into multiple branches.

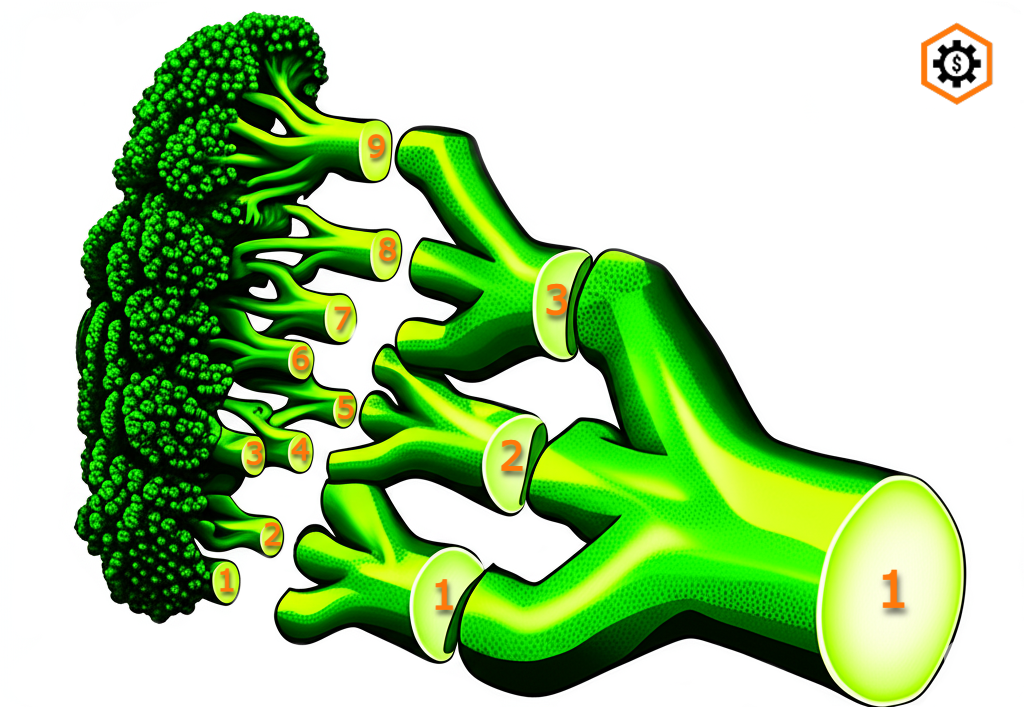

That’s what makes the family tree such a common metaphor. For this essay, we’ll use a head of broccoli instead, because it's the same shape but smaller. Stalks propagate along the length of a head of broccoli, just as human families propagate over time; a single stalk divides into several branches, which divide into still more branches.

Our broccoli metaphor is just like sheet music, where time is swapped out for distance. The length of our broccoli head represents the time signature, and cross-sectional slices along that length represent snapshots in time.

If you take a cross-section near the florets, you’ll get a cross-section of many small stems. But if you chop the broccoli in the middle, you’ll get a cross-section of a few medium-sized stems. And if you slice it at the stalk, you’ll get a cross-section with only one large central stem.

Within each cross-section, each stem appears to be a circle, totally disconnected from other circles. Only in the fullness of 3 dimensions are these individual stems revealed to be part of one continuous whole. So it is with humanity. Only in the fullness of 4 dimensions is our sense of individuality, or our ego, revealed to be an illusion.

The Geometry of the Human Story

The famous Flammarion Engraving is a woodcut by an unknown artist that dates back at least to 1888. It portrays an individual escaping from the confines of Einsteinian spacetime, as if they’re climbing under the apron of a circus tent. That psychedelic image serves as the Title Card for this essay.

The thought experiment of swapping time for distance allows us to make a similar escape of our own into the fullness of 4 dimensions, just like the figure in that woodcut. From an imaginary 4D perspective, where the future is a place that always exists, hidden from view around a corner in time, the geometry of the human story becomes obvious.

That geometry suggests a particular moral imperative. When we operate correctly, parents sacrifice on behalf of their children. Their children, in turn, do the same for their children. In this way, humankind bootstraps itself ever upward and onward into the future. All living things share this fundamental biological pattern.

But what is the opposite of a sacrifice? Instead of stocking the cupboard for the future of our species, humans have been known to steal from it. The illusion of ego motivates people to hoard resources for themselves or an ingroup, forgetting that—in the fullness of 4 dimensions—there’s really only one human family. We make a grave error by identifying with our illusory egos rather than with the whole of humankind, present and future.

Conclusion

Our interconnectedness as a species is hidden by our handicap of perceiving time as a series of snapshots, instead of as a contiguous whole. The result of this blindness is a tendency to wander through life, seeking to glorify our own individual egos, instead of the human race as a whole. Next week’s essay will focus on banking as the quintessential manifestation of that tendency.

Since you made it this far, patient reader, kindly consider hitting the ❤️ button above or below; it really helps!

Further Materials

One might compare the relation of the ego to the id with that between a rider and his horse. The horse provides the locomotor energy, and the rider has the prerogative of determining the goal and of guiding the movements of his powerful mount towards it. But all too often in the relations between the ego and the id we find a picture of the less ideal situation in which the rider is obliged to guide his horse in the direction in which it itself wants to go.

Sigmund Freud, New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, Lecture 31: The Anatomy of the Mental Personality, 1932

I find these allegories rather confusing than enlightening. I also don't buy into the idea that a sheet of music should represent a collapse of time. But that's just my personal opinion; others may feel differently.

I think I once cited Konrad Lorenz's insight that you can't be loyal to a dog because they have a short lifespan. But you can be loyal to a family of dogs, even if their characters may differ from generation to generation. I find this dissolution of the self much more understandable, even if it's projected onto dogs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIal4k5kR3k

Scarlett Johannson makes some very interesting statements about time and existence here. I don't want to say they're well-founded statements, but they do give an impression of the relativity of existence. Alexander Dugin also cites this concept of Dasein in his "Fourth Political Theory" as a concept of Heidegger, who calls for a "society-focused Dasein" in which humans perceive themselves as part of a community. This is a challenge to the methodological individualism that characterizes contemporary liberalism and the economic theory based on it.

And then there is the systemic error that involves conceiving interest as a means of ensuring economic sustainability and not as a means of enriching one's own ego...

The part about Plato / Socrates reminds me of Walt Whitman who wrote in "Song of Myself":

"Do I contradict myself?

Very well then, I contradict myself,

I am large, I contain multitudes."