Judgement Day!

How Debt Forgiveness Could Have Saved Rome

The major theme of this essay is debt forgiveness, a practice widely observed by early agricultural societies—until the Romans forfeited economic sustainability by not forgiving debts.

Key Takeaways:

A mass influx of slaves into Roman society rendered debts unpayable, while the Roman legal system automatically awarded collateral to creditors.

The forgiveness preached by Jesus was an alternative to the foreclosure process that exacerbated dangerous wealth inequality within Roman society.

After the 2008 Financial Crisis, the United States emulated Rome by opting for foreclosure instead of forgiveness.

Foreclosure

Rome’s historical arc from Republic to Empire was driven by an economic transformation. Free citizen farmers once comprised some 90% of the Roman population. But the aristocracy reserved for themselves the bulk of the land and slaves captured during extensive military conquests. They frequently combined these assets into vast slave plantations called latifundia.

But small farmers couldn’t compete with slave labor. The rise of the plantations put them out of business and forced them into default on their mortgages. Unfortunately, the collateral on those mortgages was usually their farmland itself.

During foreclosure proceedings, the unconscious logic of Roman jurisprudence systematically delivered the bulk of Rome’s farmland into the hands of already-wealthy creditors. Because the Roman legal system was focused on the precise execution of contracts, it was blind to the dire consequences of extreme wealth inequality at the societal level.

As a result, millions of propertyless people lived at the mercy of just a couple thousand elites, who owned everything. In their 1944 classic Caesar & Christ, legendary historians Will and Ariel Durant wrote, “Wealth mounted, but it did not spread; in 104 BC, a moderate democrat reckoned that only 2,000 Roman citizens owned property.”

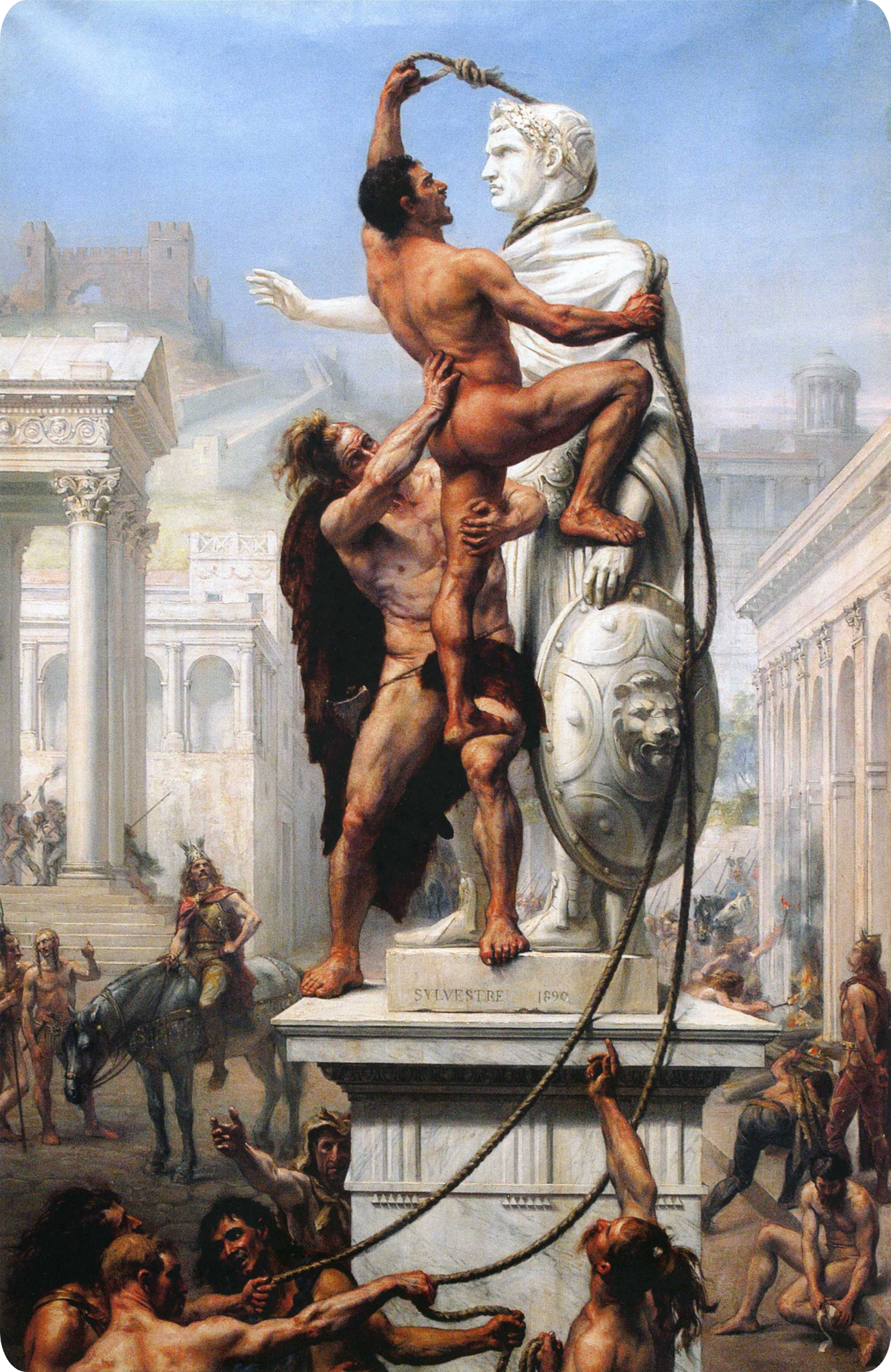

After the small farmers of Rome had been displaced by slaves, they lost any incentive to fight for a society in which they no longer had a stake. Military recruitment became a problem that the aristocracy solved by hiring foreign mercenaries, like Alaric the Visigoth. But those mercenaries eventually betrayed their masters. Alaric sacked Rome in 410 AD, and Roman civilization soon thereafter vanished from the Italian peninsula.

Forgiveness

Because they understood the danger of extreme wealth inequality, the Bronze Age kings of Mesopotamia periodically forgave debts. The Greeks, too, used forgiveness to keep debts in line with the ability of debtors to repay. But the Romans became historical pioneers by not forgiving debt, and instead upholding its sanctity with no regard for the consequences.

The Jewish inhabitants in the Roman province of Syria Palaestina, also practiced periodic debt forgiveness. That province’s most famous citizen, Jesus Christ, made forgiveness the central theme of his ministry. During his debut sermon in his hometown of Nazareth, Jesus recited a passage from Jewish scripture commanding debt forgiveness. Furthermore, his Lord’s Prayer contains the line, “Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors”.

The forgiveness advocated for by Jesus was a specific economic doctrine with a proven track record of success. It could have prevented the chaos that afflicted Rome during his lifetime. A superior legal system would have taken into account the fact that small farmers were defaulting on their mortgages through no fault of their own. If their debts had been written down to match their actual ability to pay, Rome’s free farmers could have remained on their farms instead of being forced off their property and into desperation.

Such a doctrine could have saved Rome. Instead, the aristocracy accumulated unprecedented wealth through the systematic dispossession of their countrymen. It was a recipe for social and economic chaos. Rather than embracing the forgiveness commanded by Jesus, the Romans put him to death and continued, undeterred, on their path toward the Judgment Day he warned them about.

The 2008 Financial Crisis

During the 2008 Financial Crisis, America faced a similar choice between forgiveness and foreclosure. The root of that crisis was the fraudulent issuance of subprime mortgages to borrowers who couldn’t actually afford them. The rampant sale and resale of these unpayable loan contracts imperiled the entire global financial system.

Up until 2008, the US Federal Reserve was limited to buying US Treasury bonds. But then new legislation allowed it to purchase mortgage-backed securities at face value directly from investment banks. Between 2008 and 2014, approximately $4.5 trillion of public funds was allocated to this so-called “Quantitative Easing” program.

Alternatively, the fraudulent mortgages simply could have been written down to reflect the actual ability of debtors to pay them. Though some banks certainly would have failed in this forgiveness scenario, it would have cost far less public money to bail out people rather than banks.

But, just as in Rome, wealthy creditors wield enormous influence over the American government, and they prefer foreclosure to forgiveness. Because of their policy preference, about 10% of all US mortgages went into foreclosure after 2008, and America added trillions to its National Debt.

The 2008 Financial Crisis vividly illustrated the fact that we’re still grappling with the same political and economic forces that once preoccupied Jesus Christ, and ultimately toppled the Roman Empire. Millions were kicked out of their homes—at great public expense—to preserve the wealth of yet another oligarchy. Like Rome, America is choosing foreclosure instead of forgiveness.

Conclusion

According to its own historians, Roman society collapsed because of debt. In his 2018 book ...and Forgive Them Their Debts, Dr. Michael Hudson wrote, “Livy, Plutarch and other Roman historians blamed Rome’s decline on creditors using fraud, force and political assassination to impoverish and disenfranchise the population.” Early Christianity was a reaction against this aristocratic insistence on foreclosure over forgiveness. Modern oligarchies still manage to have everything their own way, despite grave consequences that Roman history warns us about. In one of his epistles, the Roman poet Horace wrote, “Mutato nomine, de te fabula narrator.” That means, “Change the name, and the story is told about you.”

Since you made it this far, patient reader, kindly consider hitting the ❤️ button above or below; it really helps!

Further Materials

This is what the U.S. President Obama did after the 2008 crisis. Homeowners, credit-card customers, and other debtors had to start paying down the debts they had run up. About 10 million families lost their homes to foreclosure. Leaving the debt overhead in place meant stifling and polarizing the economy by transferring property from debtors to creditors.

Today’s legal system is based on the Roman Empire’s legal philosophy upholding the sanctity of debt, not its cancellation. Instead of protecting debtors from losing their property and status, the main concern is with saving creditors from loss, as if this is a prerequisite for economic stability and growth. Moral blame is placed on debtors, as if their arrears are a personal choice rather than stemming from economic strains that compel them to run into debt simply to survive.

Something has to give when debts cannot be paid on a widespread basis. The volume of debt tends to increase exponentially, to the point where it causes a crisis. If debts are not written down, they will expand and become a lever for creditors to pry away land and income from the indebted economy at large. That is why debt cancellations to save rural economies from insolvency were deemed sacred from Sumer and Babylonia through the Bible.

Michael Hudson, …and Forgive Them Their Debts, 2018, page 18