Fatal Flaw

How Wealth Addiction Creates Authority’s Lifecycles

Key Takeaways:

Christianity arose in opposition to the cruel economic hierarchy of the Roman Empire, overcame violent repression, and eventually replaced imperial authority.

Science arose in opposition to the corruption of the Roman Catholic Church, also overcame repression, and went on to replace Church authority.

Our modern authorities are growing “long in the tooth”, just like the imperial authority of Rome and Church authority during the Middle Ages.

Christianity as a Secret Society

The Greek philosopher Plato described wealth addiction as the most devastating of all addictions. Other vices, like drunkenness or gluttony, are subject to natural limits. But no amount of wealth can ever satisfy human greed. That’s because acquiring wealth instantly creates a desire for even more wealth; there’s no hangover period to limit overindulgence.

Greek tragedy is populated with characters that have a “fatal flaw” which ultimately causes their downfall. That’s exactly how Plato regarded wealth addiction. He saw this flaw as the greatest single factor shaping the trajectory of human civilization.

Plato referred to wealth addiction as “pleonexia” (πλεονεξία), and he identified it as the principal problem to be overcome in the planning of human societies and in questions of governance. Indeed, it’s the foundational concept that drives his dialogue on the ideal state in The Republic.

But even Plato couldn’t have guessed that, in the centuries following his death, the Roman Empire would dramatically emphasize his point by becoming the classic example of a society doomed by wealth inequality.

Christianity stepped onto the stage of history in opposition to the cruel economic hierarchy of the Roman Empire. As Plato might have predicted, early Christians were violently persecuted by a corrupt Roman oligarchy that had no intention of sharing its wealth.

Because of the persecution, early Christians operated as a secret society. To avoid infiltration by imperial agents, they employed secret words and symbols, like the ichthys fish that still adorns car bumpers to this day.

But as the Empire collapsed and Roman civilization vanished from the Italian peninsula, the oligarchy embraced Christianity. Emperors attempted to shore up their waning political power by converting to the popular movement. As the Middle Ages dawned, the Roman Catholic Church became a powerful new authority to replace the lapsed imperial authority in Rome.

Science as a Secret Society

With the Roman Catholic Church acting as the new authority in Europe, Christians no longer feared persecution. Nevertheless, the Church retained some of the practices of the secret society it had once been.

For example, the practice of disciplina arcani (Latin for “discipline of the secret”) meant that particular Christian doctrines were hidden from converts who had yet to be baptized. The Church’s exclusive use of archaic Latin, and the fact that few outside the clergy could read even modern languages, further hid the full scope of Christianity from its rank-and-file members.

As the Middle Ages wore on, the Church began to take advantage of the fact that most Christians had no choice but to accept whatever the clergy told them about the contents of the Bible. By the end of the Middle Ages, the Church began charging for remission of sin, a concept that had no scriptural basis whatsoever. These “Sales of Indulgences” would go on to become a bitter source of contention during the Protestant Reformation.

The Christian faith had revolted against structures of power during Roman times. But after it became the new power structure in Europe, the Roman Catholic Church inevitably became addicted to wealth like the Roman oligarchy it had once opposed. It was an effective demonstration of Plato’s principle that pleonexia is the single most perennial problem in human governance.

During the late Middle Ages, a new revolutionary movement arose to challenge the Church, as Christians had once challenged imperial authority. And just like those early Christians, early scientists were obliged to operate like a secret society to avoid persecution.

Nicolaus Copernicus was so afraid of Church authority that he published his heretical astronomical findings on his deathbed. Galileo was placed under house arrest for peering though his telescope and concluding, like Copernicus, that the earth orbits the sun, and not vice-versa as the Church insisted.

Those curious about human anatomy, like Leonardo Da Vinci, had to be very careful about dissecting human bodies. The practice was forbidden by the Church, and early medical science had to proceed under conditions of the strictest secrecy.

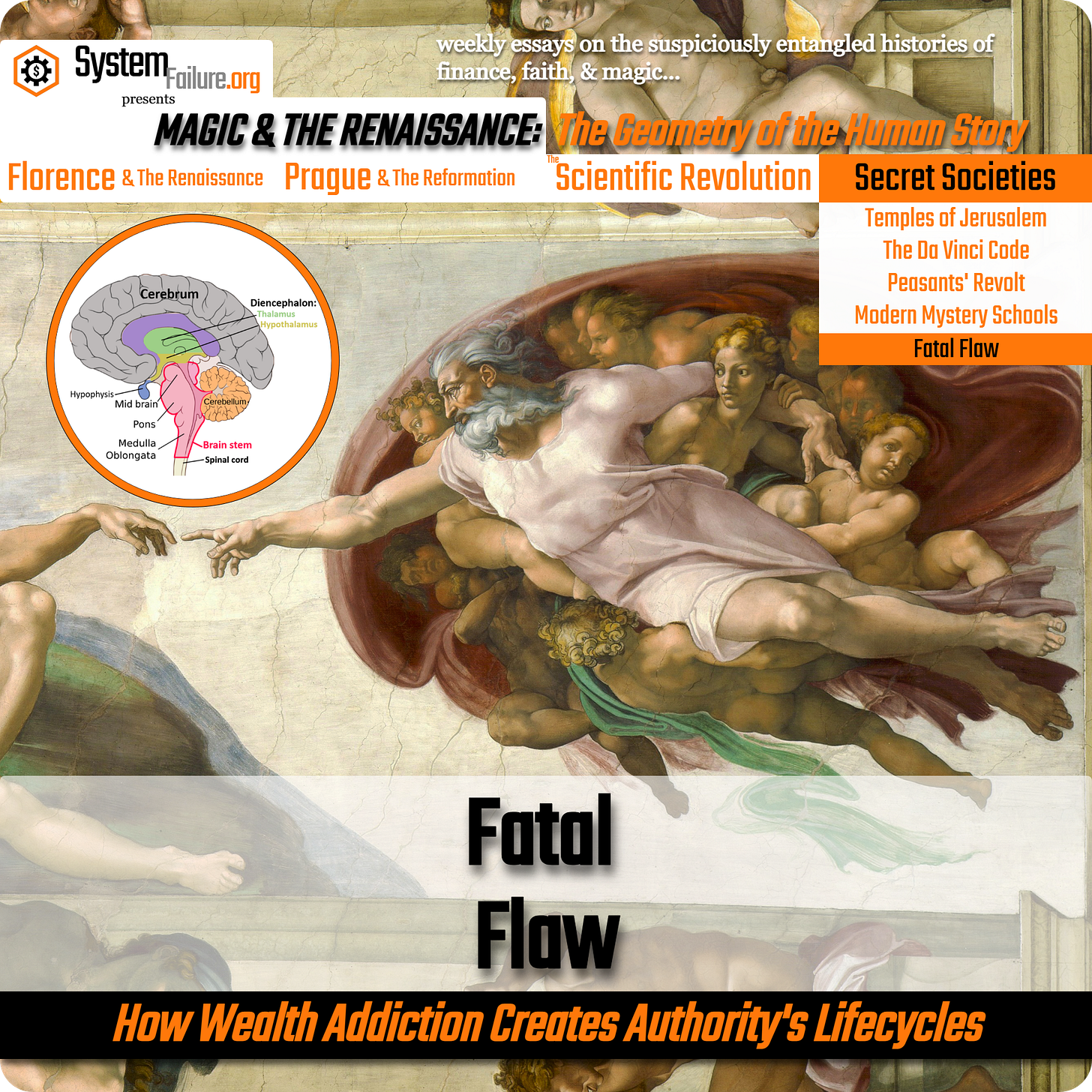

As the Italian Renaissance blossomed in Italy, Michelangelo created some of history’s most iconic paintings on the walls and ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. One prominent theory is that the shape of the cloth and figures around his representation of God closely resembles a cross-section of the human brain. A visual comparison serves as the Title Card to this essay.

The shape is so distinctive that it’s very difficult to imagine that Michelangelo created it accidentally. If indeed it was intentional, he was making a bold—but subtle—statement about the primacy of human intellect and scientific understanding during a time when the Church still wielded considerable political power. It was a move that mirrored the use by early Christians of secret symbols unrecognizable to the imperial authorities.

The Future of Banking & Science

As the Middle Ages passed into history, Europe’s stagnant feudal economy was eclipsed by a new, vibrant capitalist system. Science played an important role. Scientific innovations were brought to market by entrepreneurs as new technology. Science is the seedcorn of capitalism.

These entrepreneurs hired workers to perform the labor. And to finance their operations, they borrowed money from the banks that sprang up across Europe after the Church could no longer enforce its ban on lending money at interest.

Today, scientists, and not priests, are the ones who separate fact from fiction on behalf of the public. We trust them. The authority once enjoyed by the Roman Catholic Church was inherited by science, our modern intellectual authority. A quote from historians Will and Ariel Durant about this transition serves as the Further Materials section of this essay.

During the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church was both an economic and an intellectual authority. A significant volume of Church doctrine was devoted to economic matters. The ban on moneylending was a prime example. But in modern times, the banking system is our economic authority.

Plato pointed out that human history follows a pattern of succumbing to pleonexia. And, indeed, our modern economic authorities have become too corrupt to ignore. Wealth inequality is exploding in a manner eerily reminiscent of the late Roman Empire. The public has become wary of the big banks, whose political influence secured them bailouts instead of prosecutions after they were exposed for committing fraud on a massive scale in 2008.

Furthermore, whether rightly or wrongly, the reputation of science was badly tarnished during the recent COVID pandemic. Public trust in that institution is undeniably waning.

As another great historical epoch draws to a close before our eyes, we’re witnessing the early stages of a collapse of authority comparable to the Fall of Rome and the Late Middle Ages. Early Christians and early scientists overcame violent persecution to displace the authorities of their respective eras. The great question of our time is: from where will the next successful challenge to authority arise?

Conclusion

In boxing, great fighters experience a lifecycle. They emerge as youthful, inexperienced contenders, and the best challengers go on to become champions. But all champions are doomed to become grizzled veterans who ultimately lose their title to the next youthful, fresh-faced contender. Father Time, as they say, remains undefeated. Plato noticed a similar lifecycle in systems of governance. Both Christianity and science started out as successful challengers to the prevailing authority of their day, only to succumb to pleonexia and calcify into corrupt authorities similar to the ones they displaced.

Since you made it this far, patient reader, kindly consider hitting the ❤️ button above or below; it really helps!

Further Materials

But though the Reformation had been saved, it suffered, along with Catholicism, from a skepticism encouraged by the coarseness of religious polemics, the brutality of the war, and the cruelties of belief. During the holocaust thousands of “witches” were put to death. Men began to doubt creeds that preached Christ and practiced wholesale fratricide. They discovered the political and economic motives that hid under religious formulas, and they suspected their rulers of having no real faith but the lust for power—though Ferdinand II had repeatedly risked his power for the sake of his faith. Even in this darkest of modern ages an increasing number of men turned to science and philosophy for answers less incarnadined than those which the faiths had so violently sought to enforce. Galileo was dramatizing the Copernican revolution, Descartes was questioning all tradition and authority, Bruno was crying out to Europe from his agonies at the stake. The Peace of Westphalia ended the reign of theology over the European mind, and left the road obstructed but passable for the tentatives of reason.

Will & Ariel Durant, The Age of Reason Begins, 1961, page 571

"The great question of our time is: from where will the next successful challenge to authority arise?"

The answer is quite clear: Confucianism. This is because Confucianism pursues a different view of humanity, one based on inner virtue, morality, and respect for the community and its values. Respect for the community, in particular, is the key to a different organization of society, one that no longer adheres to the pleonexia of the financialism of Western societies. China is known as a pioneer in placing the common good above individual interests, which is evident in the arrests and harsh sentences even of members of the upper nomenklatura.

The Chinese are not afraid to bring people like Jack Ma, whose wealth has gone to their heads, back down to earth. The motto is that as long as there is poverty in their own country, everyone must contribute to changing this situation. And since there is unlikely to be a color revolution in China, these principles will shape the future.

In Russia, similar approaches are also being explored by Alexander Dugin. In his Fourth Political Theory, which is essentially inspired by Heidegger's concept of Dasein (human being as a social being), it aims to establish Russia as the "heartland" of a new political culture. While this is obscured by the current war, it can also serve as a guide for solidarity.

The outlook isn't so bad.